|

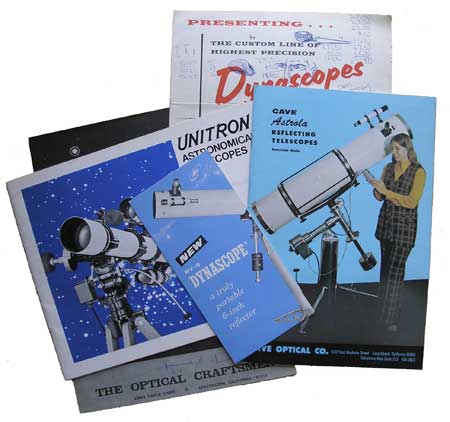

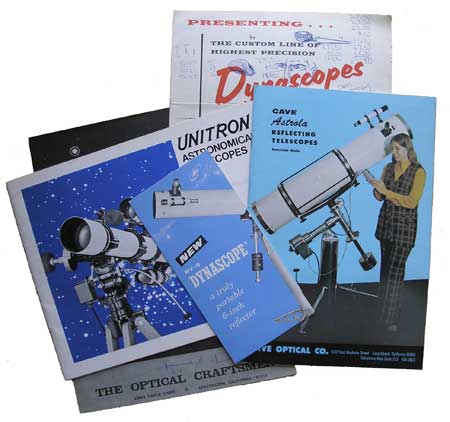

| Telescope

catalogs of yore: Unitron, The Optical Craftsmen,

Criterion (Dynascopes) and Cave Astrola. |

My

constellation-learning efforts became more systematic with the

help of a miraculous device: the Edmund Scientific Star and

Satellite Path Finder (a planisphere). This cardboard mechanism

was capable of showing where the stars would be at any given time

or date! It could actually predict their rising and setting! Now I

could really learn all those stars and constellations I'd been

reading about. The planisphere says that the great star Procyon

will rise at 10:30! Out I go...looking for a clear horizon to the

east...there it is, sparkling in the darkness! A night of wonders.

Aldebaran! Capella! The names of the stars inflamed the

imagination of someone still young enough so that every new

experience was deep and vivid. Once I convinced my parents to take

me to the house of some friends of theirs who lived in the country

so I could try my scope in a darker sky. We didn't stay long

enough for me to find anything, but I did notice a bright group of

stars near the northern horizon. "Wow," I thought, "that must be

something important." And then it clicked. Cassiopeia! Another

friend made and known.

My

constellation-learning efforts became more systematic with the

help of a miraculous device: the Edmund Scientific Star and

Satellite Path Finder (a planisphere). This cardboard mechanism

was capable of showing where the stars would be at any given time

or date! It could actually predict their rising and setting! Now I

could really learn all those stars and constellations I'd been

reading about. The planisphere says that the great star Procyon

will rise at 10:30! Out I go...looking for a clear horizon to the

east...there it is, sparkling in the darkness! A night of wonders.

Aldebaran! Capella! The names of the stars inflamed the

imagination of someone still young enough so that every new

experience was deep and vivid. Once I convinced my parents to take

me to the house of some friends of theirs who lived in the country

so I could try my scope in a darker sky. We didn't stay long

enough for me to find anything, but I did notice a bright group of

stars near the northern horizon. "Wow," I thought, "that must be

something important." And then it clicked. Cassiopeia! Another

friend made and known. |

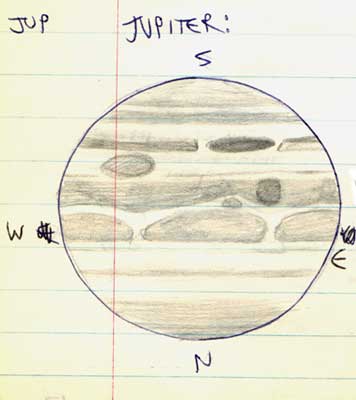

| Sketch of

Jupiter made at the eyepiece of my 3" refractor on

August 13, 1972. I wonder what I would see or draw now

if I went back and looked with the same scope at the

same time? Something better than this, I hope. |

|

| A trio of home-assembled telescopes in my back yard, circa 1975. From left to right: Remmirath, a 6" f/5 reflector; Telescopium, a 3" f/15 refractor; and Borgil, a 3" f/6.5. All three scopes experienced various redesigns to make them lighter and more portable. All three wound up with different-colored paint jobs, too. Being unable to choose the color of my scopes is one thing I miss when using commercial instruments (I have no intention of going at my A-P scopes with a spray can). |

|

| A very

orange-shirted Joe peers through his mother's new

Questar telescope in 1976. |

|

| Acrylic

self-portrait showing me observing with Telumehtar, an

8" f/5 reflector, in 1981. |

Copyright by Joe Bergeron.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|